On Lost Princesses

Bridgerton and an old favourite class trope

What do Bridgerton, Games of Thrones, Anastasia, Spaceballs, and The Lord of the Rings all have in common? They all lean on one of storytelling’s most enduring narrative devices — the lost royal orphan. Popular culture is full of characters who appear ordinary, or even socially marginal, only to discover that they are secretly heirs to the throne, or at least nobility. Jon Snow, Anastasia, Lone Starr, Aragorn all follow this trajectory. And, spoiler alert, Bridgerton fans are currently waiting for a similar revelation in the latest season.

I’ve been enjoying the online ‘discourse’ about the latest season of Bridgerton, which, using a classic form of the ‘lost princess’ trope, retells a Cinderella story in Regency England. Benedict Bridgerton, son of a viscount, falls in love with Sophie, a servant. But — through a series of exposition dumps and an appropriately villainous stepmother — it emerges that Sophie is actually the illegitimate daughter of an earl and probably wrongly disinherited. The mid-season cliffhanger saw Benedict ask Sophie to become his mistress rather than wife. Cue heated debates online about her technical social standing.

I have rarely seen such impassioned attempts to distinguish between servants, wards, bastards, secretaries, gentlemen, viscounts, and earls. There is something delightfully Austenian about watching modern audiences, totally removed from Regency social structures, attempt to reconstruct their intricate hierarchies using a series that has always treated historical accuracy with a cartload of salt.

Setting aside twitterings about entailment and Regency property law, the show nevertheless grounds part of Benedict and Sophie’s attraction in a crucial detail: Sophie was raised to be noble. She is educated, fluent in French, and comfortable discussing literature and philosophy. She lacks economic capital, but she possesses cultural capital. She is, in many ways, a reverse Eliza Doolittle.

This detail has prompted some online hand-wringing about how socially radical the relationship really is. On one hand, Bridgerton season 4 appears to offer rare attention to the ‘downstairs’ lives of servants, and Benedict’s romantic choice initially seems more socially disruptive than the comparatively well-matched pairings of earlier seasons. On the other hand, Sophie’s refinement complicates the idea that this romance genuinely collapses class barriers. The debate seems caught between two impulses. As one viewer put it on X:

I feel like Sophie and therefore the overall love story is undermined by the fact that deep down she is the daughter of a nobleman who was raised to be noble. Like that’s her ticket into the entry of society instead of forcing them to accept her even without the lineage which undermines the whole she’s a maid thing.

These concerns feel distinctly modern, rooted in contemporary conversations about assimilation, code-switching, and cultural legitimacy. Yet within literary history, the device expresses a long-standing fascination with what nobility actually means, especially when removed from wealth and status.

In my last post on Hamnet, I discussed one of my favourite Shakespeare plays, The Winter’s Tale. In the play’s second half, we meet Perdita, the lost princess of Sicily, raised by shepherds in Bohemia. Modern productions often emphasise the radicalism of her romance with the Bohemian prince, Florizel, sometimes portraying Perdita as fully indistinguishable from the rural community around her. I’ve seen productions where she speaks in a thick West Country or Cockney accent. This is, admittedly, a small pet peeve of mine. Shakespeare’s text repeatedly insists that Perdita’s nobility is visible — even when her origins are unknown. As one character remarks:

This is the prettiest lowborn lass that ever

Ran on the greensward. Nothing she does or seems

But smacks of something greater than herself,

Too noble for this place.

Perdita embodies a fantasy that true nobility expresses itself through behaviour, language, and even moral instinct, rather than wealth or formal title alone. As it appears in Shakespeare, where Perdita hasn’t received the educational nurture for modern audiences to make sense of her noble appearance, the ‘lost princess’ trope proposes that aristocratic virtue is innate, almost biological.

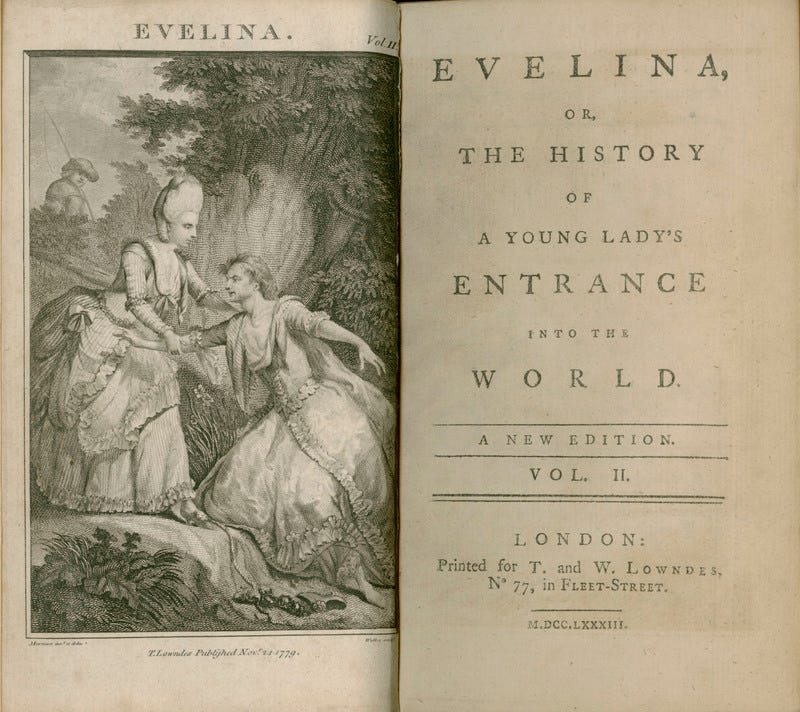

This trope flourished during Jane Austen’s era as well. Austen herself was generally too committed to social realism to indulge fully in lost-princess fantasies, but the so-called ‘sentimental’ novels that preceded her are filled with heroines who discover hidden inheritances, aristocratic families, and moral vindication through genealogical revelation. Fanny Burney’s Evelina (1778), for example, offers a parallel to Sophie’s story. Evelina grows up unacknowledged by her aristocratic father and is raised as a ward. When she eventually enters fashionable society, her ambiguous birth clashes with her polished manners. The narrative tension resolves only when her noble parentage is revealed, allowing readers to admire her refinement without fully confronting the instability of class hierarchy. As one character observes of Evelina:

She seems born for an ornament to the world. Nature has been bountiful to her of whatever she had to bestow; and the peculiar attention you have given to her education, has formed her mind to a degree of excellence, that in one so young I have scarce ever seen equalled. Fortune alone has hitherto been sparing of her gifts; and she, too, now opens the way which leads to all that is left to wish for her.

The revelation of noble birth retroactively justifies her refinement, rather than transforming her. In her excellent book, Downward Mobility: The Form of Capital and the Sentimental Novel, Katherine Binhammer traces the popularity of narratives about lost wealth and displaced aristocracy in the eighteenth century. These stories often place noble characters in situations of deprivation and moral testing. Sometimes they regain their status; sometimes they do not. Either way, these ‘‘lost princess’ fairytales’ reflect anxieties about an increasingly commercial, money-obsessed society.

These stories also dramatise a paradox about money and virtue. Characters are frequently required to reject financial advantage in order to demonstrate moral integrity — only to be rewarded with wealth and status once they have proven themselves deserving. As Binhammer notes:

The cliché that money does not buy happiness presumes commerce and virtue inhabit separate and opposed realms: the love of money and that of virtue are incommensurable.

The lost aristocrat narrative resolves this tension by allowing virtue and wealth to reunite — but only after virtue has been proven independent of wealth.

It seems almost inevitable that Bridgerton will lead Sophie and Benedict toward marriage and reintegration into elite Regency society. If the series follows the logic of its literary predecessors, Sophie’s rediscovered inheritance will likely render her socially and financially secure — perhaps even wealthier than many of the show’s established heiresses. The precise details of Sophie’s heritage matter less than they might initially appear and the supposed social transgression of their relationship will ultimately prove less radical too.

The online debates about the progressive credentials of Sophie and Benedict’s romance are revealing, but not, I think, because they hinge on the finer points of Regency class dynamics. What they expose instead is a much older preoccupation: a fascination with stories that allow us to prize virtue over wealth, while still ensuring that virtue and wealth ultimately coincide. The lost princess narrative essentially attempts to make social and economic hierarchy morally legible. These stories offer a way of thinking through social inequality without requiring its abolition.